Naphtha-based ethylene steam cracking plants are closing all over Europe. Total is expected to shut the ethylene operation at its Carling petrochemical plant in Strasbourg, France; and according to Reuters, Scotland took a blow last week when the Grangemouth petrochemical site shut down. Those decisions were forced by math so simple it could have been sketched on the back of an envelope: ruinous price competition from cheap US ethylene produced from ethane. As a matter of fact, for Europe the story gets worse. With fracking flooding America with natural gas, in just three years the split between ethane and naphtha in ethylene production flipped to 80-20 from 50-50, according to the association of American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers. And even worse. With more than 10m tons of ethylene capacity set to come online in the US by 2017, as companies like Dow Chemical and Exxon Mobil develop $25 billion worth of new projects that run mainly on ethane from shale gas, the "death knell to commodity chemical manufacturing in most of Europe" has just been rung by analysts from global auditing firm KPMG. But the next transformation of the ethylene story might be written by a small San Francisco startup, Siluria Technologies, which is on the verge of commercializing a new way to turn methane - normally cheaper than ethane - into chemicals, jet fuel, and gasoline.

Optimizing novel catalysts

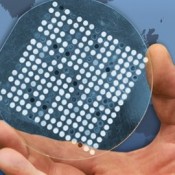

Traditionally, the world's 140 million metric tons of annual ethylene capacity is created by steam cracking, or heating feedstocks to about 800 ?C. The heat cracks both carbon-carbon bonds, creating smaller molecules, and carbon-hydrogen bonds, giving rise to the double bonds of ethylene. This is a very energy-intensive process, and between 1.5 and 3.0 tons of carbon dioxide is emitted for every ton of ethylene produced. Building on work by MIT's Dr. Angela Belcher using genetically modified

bacteriophages as scaffolds for constructing inorganic materials, Siluria is discovering and optimizing novel catalysts for the oxidative coupling of methane (OCM) reaction to produce ethylene directly from methane with high performance at low temperatures. With Siluria's biocatalysts, metals and metal oxide crystals are grown on biological templates, allowing unique ways to manipulate the surface to transform methane. This provides a path to resolving the problems of OCM. Since the discovery of the reaction in the 1980s, researchers have looked unsuccessfully for a commercially viable OCM catalyst. If Siluria's OCM process is commercially viable, it will break the connection between the production of chemicals and fuels from crude oil and its current price instabilities. It is also an exothermic reaction that requires less energy, and the heat thrown off by the reaction can be harvested to drive the process. With Siluria's technology, the conversion takes place at temperatures 200 to 300? below current steam cracking methods, reducing the energy needed to produce ethylene.

A watershed moment for the small company

Now the company is gearing up to build its first demonstration plant. To help, Siluria hired Edward Dineen as its new CEO. Dineen has vast experience in the chemical industry after being COO at LyondellBasell, one of the world's largest fuel and chemical producers with over $45 billion in annual revenue and over 58 manufacturing locations in 18 countries. He will guide Siluria out of the lab and into the marketplace. "There's going to be this long period of time when we have this excess gas," said Dineen. "If you believe that, and I do, then having technologies that give you better options for that gas would make sense." The company has been producing ethylene at lab/bench scale since early 2010 and in two pilot facilities since early 2012. It has also achieved commercial targets. Now Siluria is currently designing a demonstration facility capable of producing hundreds of tons of petrochemical products per year. Construction on the demonstration facility will begin soon and become operational by late 2014. It will be capable of producing hundreds of thousands of gallon a year. At the same time, Siluria is already engaged in discussions with chemical and fuel producers about future joint ventures and commercial relationships.