Part V - Financial Statements (Cash Flow Statement)

In the last few posts, we've talked about various Financial Statements that companies are required by law to prepare and share with stockholders and government agencies. Your bo$$, of course, shows sensitivity to operating and production costs because he or she wants these Financial Statements to be favorable. In particular, in the last blog, we discussed Income Statements at length.

Do you think if a company shows a positive Net Income that they are free of all financial trouble?

A Cash Flow Statement, like the Income Statement, shows changes in money flow during a specific period of time: a month, quarter, or year, for example. (You'll recall from an earlier post that the Balance Sheet is a snapshot in time, showing a "material balance" of Assets against Liabilities.) Cash Flow is easy to calculate. If you start the year on January 1st with $1M in cash and end the year on December 31st with $2.5M cash, the cash flow for the year is positive $1.5M.

However, it's quite possible to have a positive Net Income but a negative Cash Flow. Suppose you recently took a job as Chemical

Process Engineer and you take home $2,000 per month as Net Income. But, you've got to pay the mortgage ($1,500 per month) and the car loan ($400 per month), as well as the electricity ($100 per month) and buy groceries ($100 per month). Oops! The total of your payments out are $2,100 but you're only getting a check for $2,000. You have a negative cash flow of $100 for the month, even though you have a positive Net Income from your job as a chemical engineer.

This can happen in businesses, too. In the 1990s some very well-known companies (Boston Market, Montgomery Ward, Filene's Basement) failed even though they appeared financially healthy. The problem: insufficient cash flow. Revenue recognizes a profit from the product sold and expense to manufacture and sell it, when it is sold. But sometimes the cash from the sale is not received in the proper time frame to show a positive cash flow. Then, the business doesn't have enough cash to pay suppliers or employees and the company is at risk of failing.

Typical Cash Flow Statements classify cash inflows and outflows as:

- Financing Activities,

- Investing Activities, or

- Operating Activities.

Investing Activities include cash inflow from the sale of Plant, Property, or Equipment, and the sale of long-term securities (stocks and bonds) of other companies. Outflows would include purchases of Plant, Property, and Equipment, and making a loan as an investment (e.g. to a subsidiary company). Cash flows from Financing Activities include selling or re-purchasing stocks and bonds of your company, borrowing from banks, and repaying notes or bonds.

Operating Activities are of the most interest to Chemical Engineers, since they include acquiring and selling products in the

normal course of business. Positive cash inflow occurs from the sales of products or services, while cash outflow involves payment of operating expenses (utilities, suppliers, etc.) and payments for wages, taxes, and interest for example.

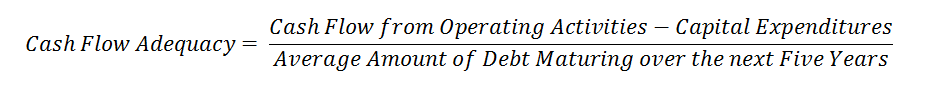

Analysts will look at a measure from the Cash Flow Statement called the Cash Flow Adequacy. This ratio helps creditors and banks determine if the company is in a position to repay its debts and meet its interest payments.

You may want to calculate this ratio when you review your company's Annual Report.

Now that you know why your bo$$ cares about Cash Flow, what other expenses can you minimize to increase profit?

What costs are not controllable?

Next time, we'll address Operating Costs, and a specific cost called Depreciation, that is directly related to whether your bo$$ will approve your capital project or not.