This post is presented by SBE, the Society for Biological Engineering--a global organization of leading engineers and scientists dedicated to advancing the integration of biology with engineering.

This post is presented by SBE, the Society for Biological Engineering--a global organization of leading engineers and scientists dedicated to advancing the integration of biology with engineering.

BP Oil Spill:

BP Oil Spill:

Just when events in the Gulf seemed dire, almost Biblical, the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, (an apt Old Testament pun) reported that oil from the BP spill was rapidly breaking down. Many scientists were skeptical-- it smelled like spin. The post-Exxon Valdez consensus was directly challenged.

But a subsequent

study led by

Terry Hazen, a microbial ecologist at the

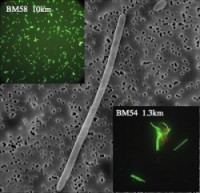

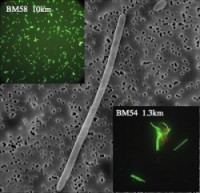

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, after analyzing 200 samples from 17 deep water sites, found that

hungry deep-sea bacteria were devouring the oil plume. LBNL's

press release said:

Analysis by Hazen and his colleagues of microbial genes in the dispersed oil plume revealed a variety of hydrocarbon-degraders... Analysis of changes in the oil composition as the plume extended from the wellhead pointed to faster than expected biodegradation rates...

Hazen, the first to study oil degradation at such depths, commented that the bacteria were well adapted to eat oil at very cold temperatures, doing their work without much oxygen-- eliminating fears of oxygen dead zones.

Also discovered, the dominant microbe in the Gulf spill was a new species, closely related to the members of the Oceanospirillales family.

Hazen's most optimistic and controversial claim: bacteria are not only devouring oil, but so much has been eaten that researchers can't find the plume.

His research, partly funded by BP, came from a pre-existing 10-year grant and wasn't involved with the spill.

Now a new

study, released by

UC Santa Barbara microbial biochemist

David Valentine and his colleagues, presents a different view. The bacteria that attacked the plumes, first digested natural gases like propane, ethane and butane-- all more easily degraded than oil. This caused the growth of bacteria that eventually digested the more complex hydrocarbons. But he's skeptical of Hazen's optimism, "It's hard to imagine these bacteria are capable of taking down all components of oil... it's more complex than that."

August 7th, two fully loaded cargo ships collide six miles outside the harbor. One ship, loaded with over 3,000 tons of oil and diesel fuel, starts leaking. The currents take the oil straight toward shore.

This post is presented by SBE, the Society for Biological Engineering--a global organization of leading engineers and scientists dedicated to advancing the integration of biology with engineering.

This post is presented by SBE, the Society for Biological Engineering--a global organization of leading engineers and scientists dedicated to advancing the integration of biology with engineering.

BP Oil Spill:

BP Oil Spill:

hungry deep-sea bacteria were devouring the oil plume. LBNL's press release said:

hungry deep-sea bacteria were devouring the oil plume. LBNL's press release said:

Also discovered, the dominant microbe in the Gulf spill was a new species, closely related to the members of the Oceanospirillales family.

Hazen's most optimistic and controversial claim: bacteria are not only devouring oil, but so much has been eaten that researchers can't find the plume.

His research, partly funded by BP, came from a pre-existing 10-year grant and wasn't involved with the spill.

Now a new study, released by UC Santa Barbara microbial biochemist David Valentine and his colleagues, presents a different view. The bacteria that attacked the plumes, first digested natural gases like propane, ethane and butane-- all more easily degraded than oil. This caused the growth of bacteria that eventually digested the more complex hydrocarbons. But he's skeptical of Hazen's optimism, "It's hard to imagine these bacteria are capable of taking down all components of oil... it's more complex than that."

Also discovered, the dominant microbe in the Gulf spill was a new species, closely related to the members of the Oceanospirillales family.

Hazen's most optimistic and controversial claim: bacteria are not only devouring oil, but so much has been eaten that researchers can't find the plume.

His research, partly funded by BP, came from a pre-existing 10-year grant and wasn't involved with the spill.

Now a new study, released by UC Santa Barbara microbial biochemist David Valentine and his colleagues, presents a different view. The bacteria that attacked the plumes, first digested natural gases like propane, ethane and butane-- all more easily degraded than oil. This caused the growth of bacteria that eventually digested the more complex hydrocarbons. But he's skeptical of Hazen's optimism, "It's hard to imagine these bacteria are capable of taking down all components of oil... it's more complex than that."

along 1.2 kilometers of beach to cripple the local tourist industry.

Authorities quickly called in The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). Director, Dr Banwari Lal, described their "magic weapon" - a technique called Oilzapper. It is a cocktail of bacteria which releases carbon-dioxide as it eats oil compounds and sludge. And after the bacteria have digested the oil, they die, becoming food for plankton or small fish.

Overseen by Dr Lal, volunteers collected oil from the first spill site in a pit and doused it with Oilzapper. "The entire area was cleaned in a day. Nothing remains but pure sand," said Banwari Lal. The remaining oil-soaked sand was removed, putting it in ditches 200 meters away from the beach. Bacteria was added, and it will take about two months to digest the oil.

along 1.2 kilometers of beach to cripple the local tourist industry.

Authorities quickly called in The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). Director, Dr Banwari Lal, described their "magic weapon" - a technique called Oilzapper. It is a cocktail of bacteria which releases carbon-dioxide as it eats oil compounds and sludge. And after the bacteria have digested the oil, they die, becoming food for plankton or small fish.

Overseen by Dr Lal, volunteers collected oil from the first spill site in a pit and doused it with Oilzapper. "The entire area was cleaned in a day. Nothing remains but pure sand," said Banwari Lal. The remaining oil-soaked sand was removed, putting it in ditches 200 meters away from the beach. Bacteria was added, and it will take about two months to digest the oil.

Munich beer hall promoters are nervous. Bavarian voters just passed a statewide smoking ban. Without smoke hiding the effects of a 16 day revelry, the noxious stench of stale beer, rotten food, urine and callow collegiate vomit-- might chase customers away.

Fortunately Oktoberfest has a one year reprieve. But nervous promoters are conducting a test this year. They've decided to pour a solution of live bacteria in three of the tents, testing it's power to obscure any offensive odors.

One owner, who has already tried the bacteria-rich concoction, say's it's worked. Marketed as "Elbomex," it's usually sold as a soil additive. The manufacturer also touts it's ability to obscure fetid waste treatment plant odors. But festival goers will be the final judges. Promoters just hope beer goggles are olfactory.

Munich beer hall promoters are nervous. Bavarian voters just passed a statewide smoking ban. Without smoke hiding the effects of a 16 day revelry, the noxious stench of stale beer, rotten food, urine and callow collegiate vomit-- might chase customers away.

Fortunately Oktoberfest has a one year reprieve. But nervous promoters are conducting a test this year. They've decided to pour a solution of live bacteria in three of the tents, testing it's power to obscure any offensive odors.

One owner, who has already tried the bacteria-rich concoction, say's it's worked. Marketed as "Elbomex," it's usually sold as a soil additive. The manufacturer also touts it's ability to obscure fetid waste treatment plant odors. But festival goers will be the final judges. Promoters just hope beer goggles are olfactory.