Mentors: nature vs nurture

Huber, who is now one of the world's leading experts on catalytic pyrolysis, summed up the breakthrough's impact": Today, we think that we can be economically competitive with crude oil production." Then he adds the societal dimension: "The ultimate significance of our research is that our green process can be used to make virtually all the petrochemical materials you can find." He finally reveals the another key part of the innovator's toolkit: finding a larger meaning.

Where did Huber find his vision? His relationship with an early mentor offers a clue. In 2005, he earned his PhD at UW-Madison under professor of chemical engineering James Dumesic. While working with Dumesic, Huber specialized in making fuel and chemicals from biomass rather than crude oil. (Start up Virent Energy Systems was spun out of this research)."When I was working on my PhD with Jim Dumesic, he said his goal in coming to the lab each day was that, if we had a good result, it would make a difference. That's the mentality there, of what research should be all about."

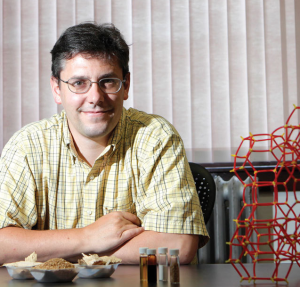

After joining the University of Massachusetts-Amherst staff in 2006, Huber helped to develop a single-step process to make olefins and aromatics from biomass using a catalytic fast pyrolysis system. Although he still considers research his main focus; he recentlyamher told

Biorefining Magazine that researchers like him are more than aware of what their work could mean. "I think it is an exciting time to be in this industry," he says. "I think there is a lot of room for growth and improving these processes."

Gallium-Zeolite fast pyrolysis

The newest catalyst may have completely upended the economics of biomass production."The whole name of the game is yield," says Huber. "What amount of aromatics and olefins can I make from a given amount of biomass? Our paper demonstrates that with this new gallium-zeolite catalyst we can increase the yield of those products by 40 percent. This gets us much closer to the goal of catalytic fast pyrolysis being economically viable. And we can do it all in a renewable way."

We think this will be the process of the future everybody will be using for biomass conversion." Huber adds, "This is a $400 billion per year market we're going after. We're making products that already fit into the existing infrastructure that don't need further refining."

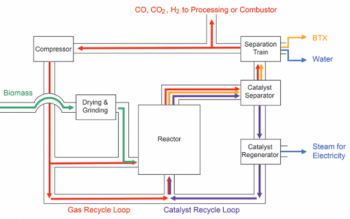

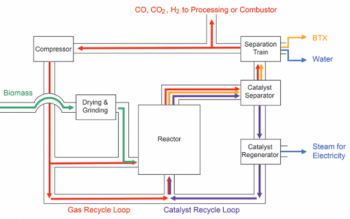

In Huber's patented single-step catalytic fast pyrolysis process, biomass is fed into

a fluidized-bed reactor, where it thermally decomposes to form vapors. These vapors then enter the team's new gallium-zeolite (Ga-ZSM-5) catalyst, also inside the same reactor, which converts the vapors into the desired chemicals. The economic advantages of the new process are threefold. All of the chemistry occurs in a single reactor; the process uses an inexpensive catalyst; and aromatics and olefins are produced that fit easily into existing petrochemical infrastructures.

Finding a higher calling

To scale up the process to industrial size for the petrochemical industry, the catalytic fast pyrolysis technology has been licensed to New York City's Anellotech, Inc., co-founded by Huber. Again, he reveals his vision for the future to his

alma mater:

"The economics only make sense at large scale, so we need to be processing 2,000 to 3,000 metric tons of dried biomass per day in the biorefinery," Huber says. "You would build the biorefinery in rural locations close to the source. I live in New England. In Maine, we have a lot of paper mills that have been shut down. So we can go to locations like that, that are economically depressed, and build these biorefineries to give a boost to these rural economies."

Improving rural economies, building a more sustainable environment; few researchers try to make such an impact through their work. For Huber, it is the role of the engineer to provide solutions.

Using this new catalyst, how close is the catalytic fast pyrolysis technology to going commercial? "Close," says Huber.

Photo: Huber at desk - Umass, John Solem/ Bioengineeringmagazine Graphic: Process schematic, Anellotech Photo: Huber holds flask: Umass Photo: Huber in lab - Umass

For several years, chemical engineer George Huber has had a great story to tell. His research team can take wood, grasses, or any other renewable biomass and create five of the six petrochemicals that serve as the building blocks for the chemical industry. And he's just made another major breakthrough.

But first, before any big news, whenever he talks to reporters, he'll toss out a personal anecdote about a slight quirk he picked up as an undergrad--his love of oil refineries. Once he started studying how they worked, he was hooked."My family laughs at me because I just love petroleum refineries,"he'll say. "Most people think of them as these dirty, awful places, but I think they are beautiful, complex, highly integrated systems."

Then he'll mention - keeping the suspense building - that in the mid-90s, soon after falling in love with oil refineries, he met a researcher who told him about about the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. "In my mind that was the coolest idea possible. I spent as much time as I could in the lab trying to learn about it." So, like all love relationships, it's complicated.

For several years, chemical engineer George Huber has had a great story to tell. His research team can take wood, grasses, or any other renewable biomass and create five of the six petrochemicals that serve as the building blocks for the chemical industry. And he's just made another major breakthrough.

But first, before any big news, whenever he talks to reporters, he'll toss out a personal anecdote about a slight quirk he picked up as an undergrad--his love of oil refineries. Once he started studying how they worked, he was hooked."My family laughs at me because I just love petroleum refineries,"he'll say. "Most people think of them as these dirty, awful places, but I think they are beautiful, complex, highly integrated systems."

Then he'll mention - keeping the suspense building - that in the mid-90s, soon after falling in love with oil refineries, he met a researcher who told him about about the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. "In my mind that was the coolest idea possible. I spent as much time as I could in the lab trying to learn about it." So, like all love relationships, it's complicated.

refinery work-around, a biomass-to-biofuels technology that, if perfected, would help to wean the US off oil. He told his alma mater: "My lab is dedicated to making sustainable liquid fuel and chemicals..." And, by the way, doesn't Huber describe a refinery the same way as Jobs would a Mac: "beautiful, complex, highly integrated systems."

With listeners now primed for the latest news, Huber announces reaching a personal milestone (press release): that his University of Massachusetts Amherst lab has developed a new fast pyrolysis catalyst that boosts biomass yields for five key "building blocks of the chemical industry" by a remarkable 40 percent over previous catalysts. This is outlined in a paper published in the German Chemical Society's journal Angewandte Chemie. Watch Huber explain single-step catalytic fast pyrolysis this 2009 lab video:

refinery work-around, a biomass-to-biofuels technology that, if perfected, would help to wean the US off oil. He told his alma mater: "My lab is dedicated to making sustainable liquid fuel and chemicals..." And, by the way, doesn't Huber describe a refinery the same way as Jobs would a Mac: "beautiful, complex, highly integrated systems."

With listeners now primed for the latest news, Huber announces reaching a personal milestone (press release): that his University of Massachusetts Amherst lab has developed a new fast pyrolysis catalyst that boosts biomass yields for five key "building blocks of the chemical industry" by a remarkable 40 percent over previous catalysts. This is outlined in a paper published in the German Chemical Society's journal Angewandte Chemie. Watch Huber explain single-step catalytic fast pyrolysis this 2009 lab video: a fluidized-bed reactor, where it thermally decomposes to form vapors. These vapors then enter the team's new gallium-zeolite (Ga-ZSM-5) catalyst, also inside the same reactor, which converts the vapors into the desired chemicals. The economic advantages of the new process are threefold. All of the chemistry occurs in a single reactor; the process uses an inexpensive catalyst; and aromatics and olefins are produced that fit easily into existing petrochemical infrastructures.

a fluidized-bed reactor, where it thermally decomposes to form vapors. These vapors then enter the team's new gallium-zeolite (Ga-ZSM-5) catalyst, also inside the same reactor, which converts the vapors into the desired chemicals. The economic advantages of the new process are threefold. All of the chemistry occurs in a single reactor; the process uses an inexpensive catalyst; and aromatics and olefins are produced that fit easily into existing petrochemical infrastructures.